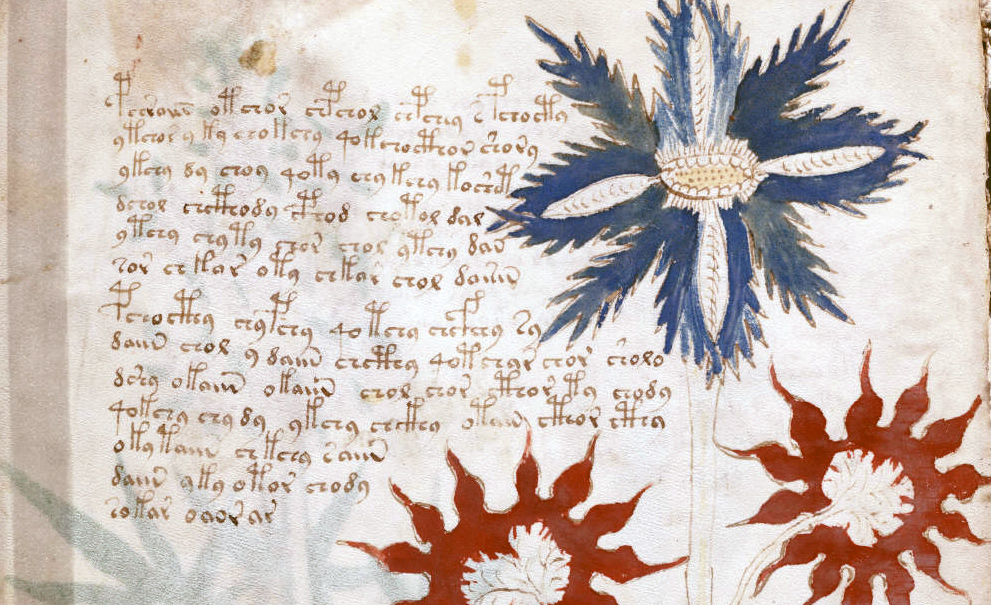

The ‘look don’t touch’ treatment may have been understandable, but the ‘seen and not heard’ addendum was an unnecessary stricture, turning me from a would-be suitor into a Voynich voyeur. I attempted to ask a few unprobing questions about how often the volume was shown and to whom, only to be met with complete silence. This inadequacy was compounded by the aloofness of my bibliographic minder. The session lasted about forty-five minutes. I struggled to find something of the everyday in it, but felt, like others, that some coherent meaning would emerge if only I looked long and hard enough. The collection of plants seemed gaspingly surreal, the naked nymphs, whether splashing in ponds or disported on starwheels, sensually whimsical, the medicine jars voluptuously oriental. Regardless of one’s acquaintance with ancient volumes, Mary D’Imperio was right to state that the Voynich manuscript stands ‘totally apart’ from other ‘remotely comparable documents’.Įach page (or folio, as I learned to term them, recto facing, verso on the other side) that librarian Ellen Cordes turned, as we progressed through the various sections, revealed fresh wonders for which I had no reference points of any kind. But somewhere at the back of my mind I possessed images of such rarities, of exotic embellishments to first-line letters or the stylised perspectives of scenes and figures that unfolded as part of a recognisable story. Initially, the sheer privilege of being granted an audience with the volume was excitement enough I had never before sat reverentially in front of any book, let alone a medieval tome. In July 2001, having travelled up from the Big Apple to Yale University to inspect the fabled Voynich manuscript, I was hoping to gain a clear and calm overview of its delights that up until then had been supplied remotely by a computer screen.

The realisation of a fantasy is proverbially fraught the long-sought-after has a habit of failing to live up to the dream, and, to make things worse, is subject to the fickle vagaries of a first impression. Gerry Kennedy once again takes up the story of his visit to Yale. Both authors were consultants for the BBC/Mentorn Films documentary The Voynich Mystery.

#VOYNICH MANUSCRIPT HIGH RESOLUTION PROFESSIONAL#

Rob Churchill is a professional writer who has written scripts for many production companies, including the BBC and Thames Television. Gerry Kennedy is a freelance writer and has produced a number of BBC Radio 4 programs, including one on the Voynich Manuscript in 2001. With the possibility that it may be a lost alchemical text or other esoteric work, this manuscript remains one of the most intriguing yet enigmatic documents ever to have come to light.

They trace the speculative history of the manuscript and reveal those who may be connected to it, including Roger Bacon, John Dee, and the Cathars. Gerry Kennedy and Rob Churchill explore the mystery surrounding the Voynich Manuscript, examining the many existing theories about the possible authors of this work and the information it may contain. Written in an unknown language or an as yet undecipherable code, this medieval manuscript contains hundreds of illustrations of unknown plants, cosmological charts, and inexplicable scenes of naked “nymphs” bathing in a green liquid that some interpret as a symbolic depiction of human reproduction and the joining of the soul with the body. Since its discovery by Wilfrid Voynich in an Italian monastery in 1912, the Voynich Manuscript has baffled scholars and cryptanalysists with its unidentifiable script and bizarre illustrations. Includes color images from the manuscript juxtaposed with other medieval writings.

#VOYNICH MANUSCRIPT HIGH RESOLUTION CODE#

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)